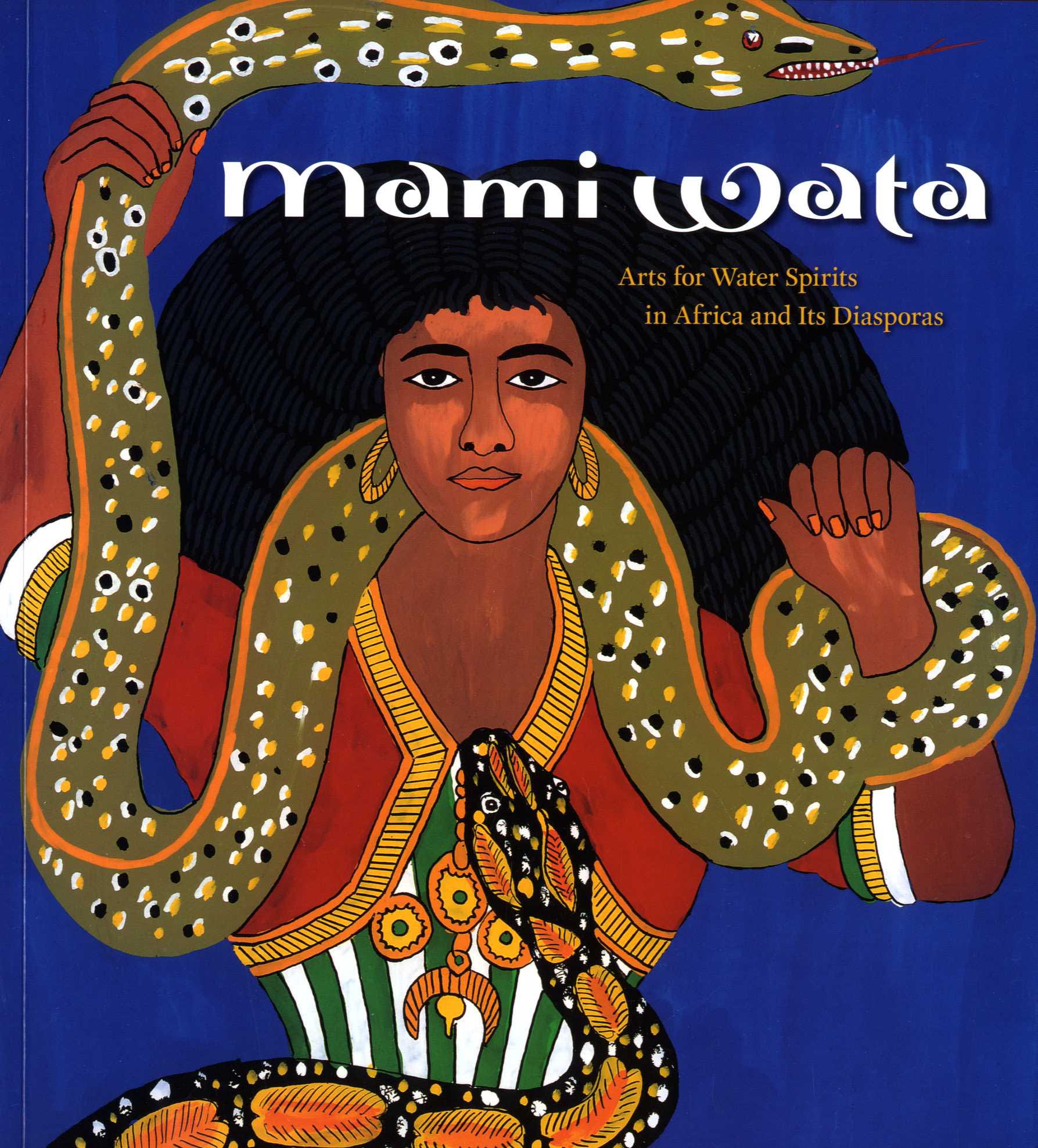

Art’s inspiration easily crosses borders, across space and time, the present exceptional ‘Mami Wata’ headdress being a perfect example. For too long African material cultures have been considered as closed systems without any outside influences; yet the origin of their inspirations, as we will see, can go way beyond the usual. ‘Mami Wata’ is such a unique pan-African phenomenon with a long and global history. The artist who carved this magnificent Ibibo headdress from Nigeria was inspired by a then 50-year-old German postcard of an Indian snake charmer active in Hamburg and abroad in the 1890s. The iconography struck a chord and was explicitly copied in a syncretic iconographic style, blending Ibibio stylistic elements with the outside influence. The theme of Mami Wata, appears in myriad forms, including mermaid and snake charmers, with varying devotional practices through sub-Saharan Africa. Henry John Drewal’s 2008 publication “Mami Wata – Arts for Water Spirits in African and Its Diaspora”, coinciding with an exhibition at the Fowler Museum at UCLA in Los Angeles, gives an excellent overview of this phenomenon.

‘Mami Wata’, which can be translated as ‘Mother Water’, is in fact pidgin English. She is said to bring good fortune in the form of money. Her powers, however, extend far beyond economic gain. Although for some she indeed bestows good fortune and statues through monetary wealth, for others, she aids in concerns related to procreation (infertility, impotence, or infant mortality). Mami Wata also provided a spiritual and professional avenue for women to become powerful priestesses and healers of both psycho-spiritual and physical ailments and to assert female agency in a generally male-dominated societies. Henry Drewal called her a multivocal, multifocal symbol with so many resonances that she feeds the imagination, generating, rather than limiting, meanings and significances: nurturing mother; sexy mama; provider of riches; healer of physical and spiritual ills; embodiment of dangers and desires, risks and challenges, dreams and aspirations, fears and forebodings. People were attracted to the seemingly limitless possibilities she represents, and at the same time frightened by her destructive potential. She inspired a vast array of emotions, attitudes, and actions among those who worshipped her, those who fear her, those who study her, and those who create works of art about her. What the Yoruba people say about their culture is also applicable to the histories and significances of Mami Wata: she is like ‘a river that never ends’. (op. cit., p. 25).

The story of this sculpture starts in Hamburg, Germany. The West has had a long and enduring fascination with the ‘exotic’. By the second half of the nineteenth century, this interest had spread beyond the European upper classes to a much wider audience. Institutions such as botanical and zoological gardens, ethnographic museums, and circuses and ‘people shows’ provided opportunities to come in touch with the exotic and bizarre. One of the most significant centers for these developments was the northern German port and trading center of Hamburg, which was in many ways Europe’s gateway to the exotic. It was an important member and leader of the Hanseatic League, a group of wealthy independent city-states on the North Sea that developed powerful import/export companies with vessels that plied the world’s oceans. Hamburg’s contacts with distant lands fed the popular European appetite for things foreign. While illustrated accounts of adventures abroad proliferated in books, magazines, and newspapers, the exotic became tangible as a growing number of African, Asian, and Indian sailors appeared in the port of Hamburg and other maritime centers. (op. cit., pp. 49-50).

Carl. G. C. Hagenbeck worked as a fish merchant in St. Pauli in the port area of Hamburg. This area was also a popular entertainment center for sailors and others. In 1848, a fisherman who worked the Artic waters brought some sea lions to Hagenbeck, which he in turn exhibited as a zoological attraction. The immediate success of this venture led to a rapidly enlarged menagerie of exotic animals from Greenland, Africa, and Asia. Sensing the public’s enormous appetite for the bizarre, Hagenbeck decided to expand his imports to include another curiosity: exotic people. The first of these arrived in 1875, a family of Laplanders, who had accompanied a shipment of reindeer. This was the modest beginning of a new concept in popular entertainment known as the ‘Völkershauen’, or ‘people shows’. In order to advertise his new attractions, Hagenbeck turned to Adolph Friedländer, a leading printer who quickly began to produce a large corpus of inexpensive color posters for Hagenbeck, whose most extravagant spectacle was doubtless his ‘International Circus And Ceylonese Caravan’, seventy artists, craftspeople, jugglers, magicians, and musicians together with many wild animals. A caravan that was witnessed by over a million people within a six-week period.

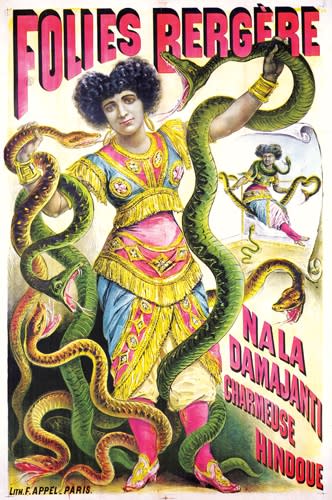

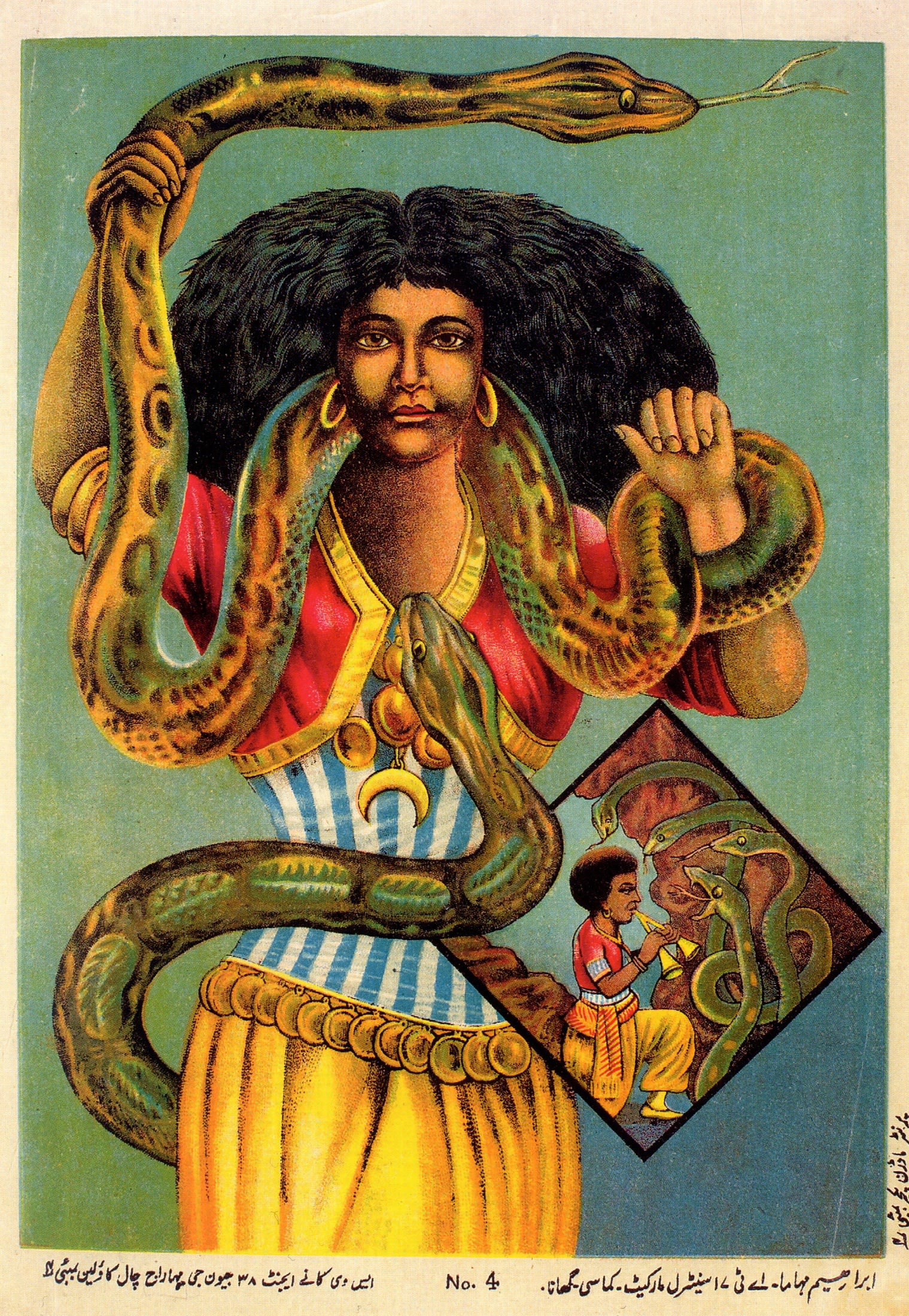

Hagenbeck hired a famous hunter named Breitwiser to travel to Southeast Asia and the Pacific to collect rare snakes, insects, and butterflies. In addition to these, Breitwiser, brought back a wife, who under the stage name ‘Maladamatjaute’ began to perform as a snake charmer in Hagenbeck’s production. A Hamburg studio photography taken about 1887 shows Maladamatjaute attired for her performance. The style and cut of her bodice, the stripes made of buttons, the coins about her waist, the armlets, the position of the snake around her neck and a second one nearby, the nonfunctional bifurcated flute held in her hand, and her facial features and coiffure: all duplicate those seen in a snake charmer chromolithograph from the Friedländer lithographic company, the original of which has not yet been found. What we do have, however, is a reprint, made in 1955 in Bombay, India, by the Shree Ram Calendar Company from an original sent to them by two merchants in Kumase, Ghana. There can be little doubt, therefor, that Maladamatjaute was the model for the image. Her light brown skin placed her beyond Europe, while the boldness of her gaze and the strangeness of her occupation epitomized for Europeans her ‘otherness’ and the mystery and wonder of the ‘Orient’. As Maladamatjaute’s fame as a snake charmer spread, her image began to appear in circus flyers and show posters for the Folies Bergères in Paris, as well as in the United States. Soon after, and probably unknown to Maladamatjaute, her image spread to Africa – but for very different reasons and imbued with very new meanings. (op. cit., pp. 50-52). In the nearly one hundred years since the arrival of the snake charmer print in Africa (and especially after twelve thousand copies were printed in Bombay, India, in 1955, and sent to traders in Kumase, Ghana), the image has traveled widely, first in West and subsequently in Central Africa. Various copies of copies continue to circulate widely in sub-Saharan Africa, where, as of 2005, Henry Drewal discerned the influence of the print in at least fifty cultures in twenty countries! (op. cit., p. 54).

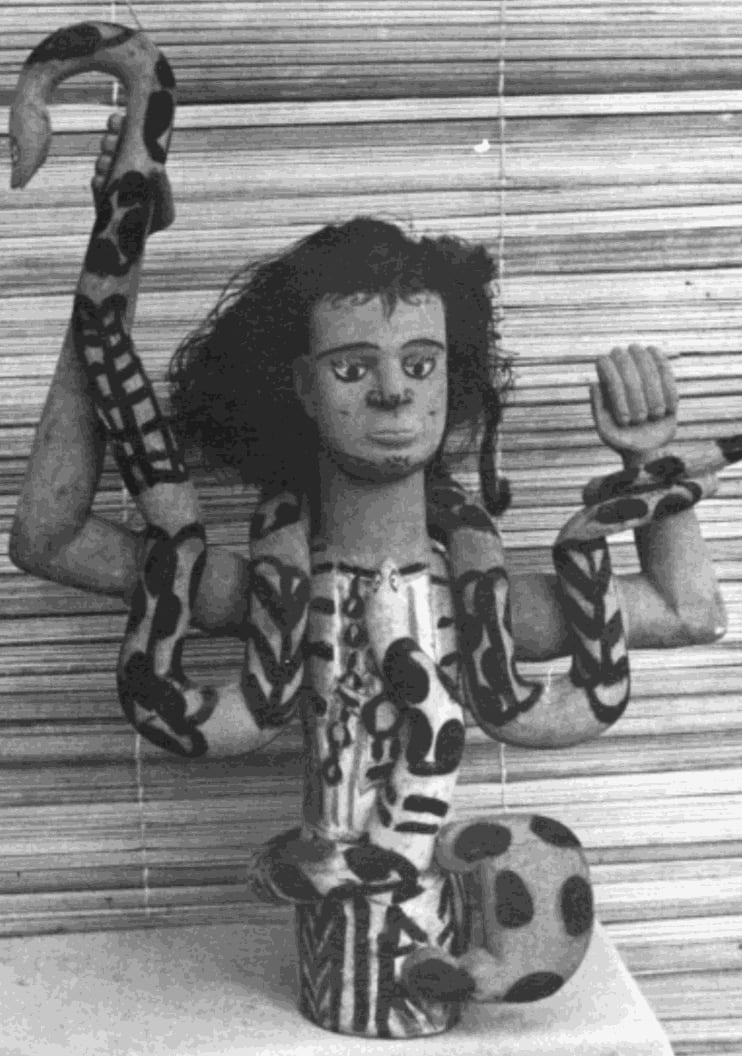

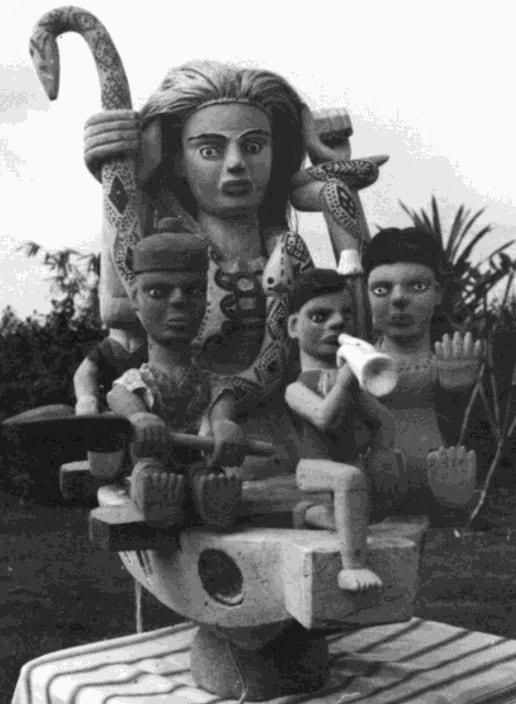

Niger River Delta water spirit headdress that was photographed by J. A. Green in the Delta town of Bonny in 1901.

Not long after its publication in Europe, the snake charmer chromolithograph reached West Africa, probably carried by African sailors who had seen it in Hamburg. European merchants stationed in Africa, whether Germans or others, may have also brought Maladamatjaute’s seductive image to decorate their work or domestic spaces. For African viewers, the snake charmer’s light brown skin and long black wavy hair suggested that she came from beyond Africa, and the print had a dramatic and almost immediate impact. By 1901, about fifteen years after its appearance in Hamburg, the snake charmer image had already been interpreted as an African water spirit, translated into a three-dimensional carved image, and incorporated into a Niger River Delta water spirit headdress that was photographed by J. A. Green in the Delta town of Bonny. The headdress clearly shows the inspiration of the Hamburg print. The image of Maladamatjaute, the ‘Hindoo’ snake charmer of European renown, had begun a new life as the primary icon for Mami Wata, an African water divinity with overseas origins. The snake, an important and widespread African symbol of water was a most appropriate subject to be shown surrounding, protecting, and being controlled by MamI Wata. Golder armlets, earrings, neckline, pendant, and waist ornaments in the print combined to evoke the riches that Mami Wata promises to those who honor her. This theme of wealth that underlies much of Mami Wata worship is sometimes exaggerated in her sculpted images, as in the present Ibibio sculpture. (op. cit., pp. 52-53).

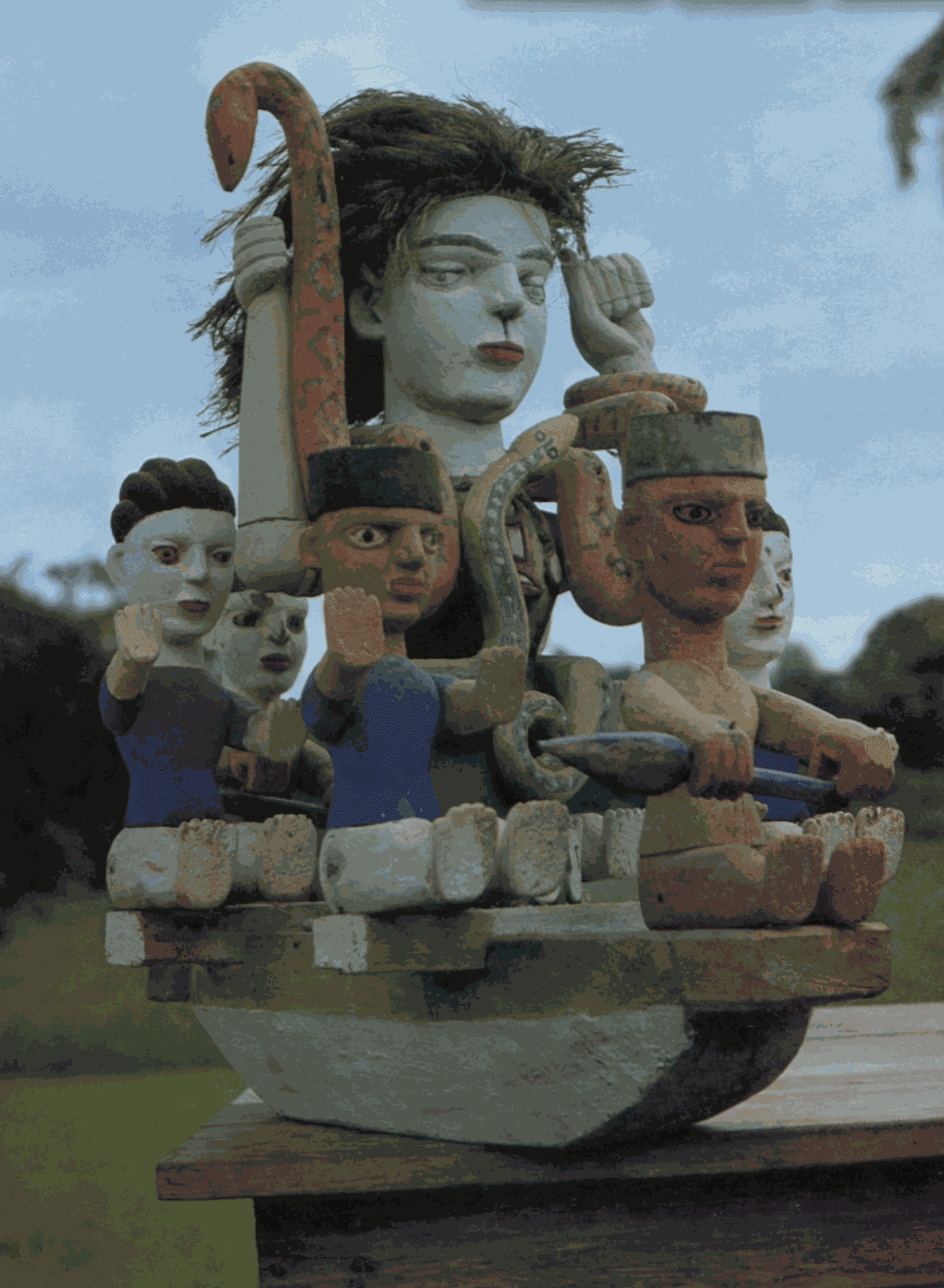

Mammy Wata commissioned by Jill Salmons for Pamela J. Brink from Thomas Chukwu in 1975. Collection of the University of Iowa Museum of Art (#1991.225).

In the 1930s and 1940s, Kenneth Murray, the first surveyor of the Nigerian Department of Antiquities, made an exhaustive survey of the arts of southeastern Nigeria. While noting the decline in carving among many Ibibio groups, largely due to intense Christian missionary activity , he remarked that the Annang continued to produce a wealth of carvings and supplied them to neighboring groups. A number of carvers lived in the important Annang trading center of Utu Etim Ekpo and sold their works from home. Murray mentioned only one ‘Mammy Wata’ carving, however, produced by Utu Etim Ekpo’s most famous carver, Akpan Chukwu. In 1944 Chukwu showed Murray a life-sized, seated, clothed Mammy Wata holding snakes, which had been commissioned by the people of Degema nearly 130 kilometers aways.

Although Akpan died in 1952, his brother Joseph informed Jill Salmons in 1975 that Akpan was first shown the German snake charmer print when a British District Officer (possibly G. F. Hodgson) commissioned a carved a representation of it from him around 1909. Akpan later elaborated the theme of Mammy Wata, creating a wide variety of forms that could be used in a number of contexts and sold to many different groups. He was often asked to produce unusual or spectacular carvings to amuse audiences, and he may well have carved the kinetic life-sized ‘Marmee Wata’ that American anthropologist John Messenger observed in the 1950s being used by a local Ekong group: ‘The figure whose bewildering movements climaxes the Ekong performance represents the female fertility spirit who resides in a number of abodes including shrines, ant hills, and streams. In this context, she is portrayed as river nnem (spirit) with a python wrapped around her arms, waist and neck, and she is known as ‘Marmee Water’ (‘mother eka in the water’). (op. cit., p. 121).

These figures are grouped to demonstrate the carving sequence followed by Akpan Chukwu and other members of his family. They were carved by Akpan Akpan Chukwu, son of the famous Annang carver Akpan Chukwu, and commissioned by the Oron Museum. Collection Oron Museum, Nigeria. Photographed by Jill Salmons, 1976.

Working in southeast Nigeria during the first two decades of the twentieth century, English District Officer P. Z. Talbot and his wife, Dorothy, provided the first clues to the importance of Mammy Wata in the pre-Christian beliefs of Ibibio peoples. The Talbots described how Eka Abassi, Mother of God, was central to fertility and lived in water, protecting people while they bathed, washed clothes, or fished. Young girls were led to a pool or stream to receive her blessing before undergoing the ritual period of education and ‘fattening’ that preceded marriage. Also known as Nnem Mmo (literaly ‘water spirit’), Eka Abassi could assume the appearance of a crocodile that was sometimes escorted by leopards, pythons, or huge fish. Neither of the Talbots, however, mentioned a carved representation of the spirit, nor does she appear to have been called ‘Mammy Wata’ at this time – as observed by John Messenger in the 1950s. His research suggests that by that time Mammy Wata had become the popular name for Eka Abassi / Nnem Mmo. It would appear that by the 1940s the newly introduced carved representation of Mammy Wata, based on the snake charmer print, served to gel previously diffuse visual representations of Eka Abassi and was preferred by the diviners for placement in her shrines. In opposition to the zeal of various missionary groups in the area, the belief in Mammy Wata and her powers acquired an almost cult like status by the 1970s with many Mammy Wata shrines being built. (op. cit., p. 117 & p. 121).

Although Mammy Wata could bestow great riches, she could also wreak havoc according to her whim. She could possess men and women and lure them to her watery kingdom while they were bathing or entice them to follow her through fantastic dreams. Her devotees might take on an otherworldly appearance and behave strangely. While they could become wealthy, they would be unable to bear children, a decided disadvantage in a culture that prizes fecundity. Some people, however, reveled in their communication with the spirit and became Mammy Wata priests or priestesses in their own right. Great wealth and prestige could accrue to priests and priestesses from creating private ‘hospitals’ where impotent men, barren women, and those suffering from mental problems would pay high fees to be treated using various modalities, including drugs and lengthy counseling sessions. Furthermore, traditional Ibibio society is male dominated, and the ability of a woman to be possessed by Mami Wata, and become a priestess, offered her a unique opportunity to achieve a status in the community equivalent to that accorded to men. (op. cit., pp. 122-123).

The completed Mammy Wata sculpture by Akpan Akpan Chukwu. Collection Oron Museum, Nigeria. Photographed by Jill Salmons, 1976.

The commissioning of carvings for these many Mammy Wata adherents explains their prevalence in the 1970s. Members of the Chukwu family, who produced many such carvings, perpetuated Akpan’s unusual carpentry style of using precise measurements to carve individual segments of the sculpture, which were then nailed together. The typical hair covering for the Mammy Wata figure was made from the dried fibers from a plantain stem. Keith Murray wrote of the Mami Wata sculpture by Akpan Chukwu: ‘He did not properly understand the print which had a subsidiary picture of the snake charmer in a small inset. Hence in his figures of Mammy Wata there is a curious excrescence on one side which actually represents the small inset picture on the print’. Akpan’s son, Akpan Akpan Chukwu, who was taught to carve by his father, still portrays this very strange ‘excrescence’ that represents the original inset picture. The statue Akpan showed Murray in 1944 was a life-sized, seated, clothed female Mammy Wata, while his brother Joseph and son Akpan Akpan carved many varieties of Mammy Wata in different sizes and poses: seated, standing, or travelling in a canoe flanked by paddlers. Joseph told Jill Salmons that because the carving of Mammy Wata was a complex piece of work, involving various carved segments that have to be joined, apprentices were often taught how to make the less complicated sections, for example, the pieces of snake that wind around the spirit’s body. The master carver would instruct his apprentices over the carving of these small units, while he himself made the central trunk and head of the figure. Joseph was taught in this way by his brother and at that time still used the same proportions that his brother originally showed him, which are carefully worked out in pencil on the wood before carving. (Salmons, Jill, “Mammy Wata”, African Arts, Vol. 10, No. 3, April 1977, p. 13).

Mammy Wata group in a canoe, carved by Joseph Chukwu. Collection Oron Museum, Nigeria. Photographed by Jill Salmons in October 1976.

In the olden days, a carver would generally be invited to work for a period of time in one village, carving all the necessary masks and figures required by the various cult groups and individuals in the village. He could also be commissioned to make certain sculptures in his own home. On completing commissioned works, Akpan Chukwu would send small boys to deliver them. Before setting out with a Mammy Wata carving, however, the boys would be given twelve to fifteen eggs; before they crossed a stream, they had to throw an egg into the water to appease the water spirit so that they could cross safely. Once the carving was delivered, the boys would be given a white cock, in addition to the financial payment, to take back to the carver. Chukwu would sacrifice the cock on his own carving shrine, for it was believed that unless he did this, the owner of the carving would not be able to satisfy the future demands of the Mammy Wata spirit. In Akpan Chukwu’s compound, Jill Salmons once witnessed eight identical Mammy Wata carvings. Salmons presumed that he had made them for traders in Ikot Ekpene, to be sold to tourists, but Chukwu informed her that in fact they had all been ordered by one diviner. The carver explained that only one was for the diviner’s personal use; the other seven were for people ‘worried’ by the spirit and who had gone to the diviner for advice on having their own shrines. Being Christians, they couldn’t erect shrines in their own compounds for fear of repercussions from their churches who expel members known to be maintaining ‘pagan’ traditions and burn any traditional shrines they come across in their compounds. By keeping their own shrines at the diviner’s compound, however, these followers were able to make the necessary sacrifices to the water spirit without incurring the wrath of their fellow Christians. (op. cit., p. 13).

Mammy Wata sculpture ensemble carved by Joseph Chukwu of Utu Etim Ekpo. Collection Jill Salmons, USA.

Akpan’s genius lay in his ability to grasp new ideas when they were presented to him – as in the case of the Mammy Wata print. A quarter of a century after the death of Akpan Chukwu in 1951, sculptors in the region conveyed to Jill Salmons he was the greatest Annang carver of his time and that he had not yet been surpassed. He had a powerful influence over a wide geographical area for a considerable period of time. Apart from influencing his immediate family and the carving styles around Utu Etim Ekpo, Salmons learned of numerous cases where artistically inclined youths watched Chukwu work when he was employed by villages in Igboland and the Niger Delta. Such youths then continued to carve in their own area after Chukwu had returned home, thus perpetuating his style over a wide area. He was, according to Keith Murray, ‘the leader of the modern style of carving, and so was appreciated most by semi-literates who where taken in by his ‘realism’, fantasy and bright colours, and preferred his carvings to the traditional carvings’. Akpan, according to his brother Joseph, was a larger-than-life character, who always carved with a bottle of imported gin or whiskey clasped between his knees. It is possible that his incredible popularity as a carver may have led to his death – it is claimed that he was poisoned by a jealous carving relative. It was Chukwu who first introduced the idea of commercializing his art by displaying prepared carvings at the front of his compound to attract passing traders to order from him; the other members of his family followed his example. In 1946, a local newspaper wrote: ‘John Chukwu, the owner of the carving venture, marries many women who do the painting after he has finished carving these things’. In the past, women were not allowed to go anywhere near a carver while he worked, the main reason being that they were not supposed to know that masks and figures used by the all-male secret societies were made by mortal hands. Later, possibly through his emancipating influence, carvers’ wives and children throughout Annangland helped in the production of carvings. Sons carved the more easily made parts, while women and young children sandpapered and painted the final pieces. (op. cit., p. 15).

Mammy Wata figure sculpted by John Onyok (active 1930´s-1970´s, Urua Akpan. Collectionv Nickl Art Foundation, Kansas City, MO, USA (#20.15.1).

In case you were even more curious about the woman who inspired the iconography, Jill Salmons (op. cit., p. 212) was able to reconstruct part of Maladamatjaute’s life. As Breitwiser did much of his ‘hunting’ in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, it seems likely that his wife came from that part of the world, possibly from Samoa or Bornea. Soon after she arrived in Hamburg with Breitwiser, about 1880, she began to perform as a snake charmer in one of Hagenbeck’s shows. She may have been taught by Breitwiser, who went by the nickname ‘snake gripper’. Within a short time she had become an international attraction, performing in the United States about 1885. A circus newspaper published in Philadelphia in 1885 shows her in a small fenced area surrounded by many snakes and holding aloft two large snakes above her head, while another wraps around her body. Her full head of hair flares outward, parted in the middle, and her name has changed to ‘Nala Damajanti – the Empress of the Reptile World – the Greatest and Most Astounding snake charmer of Hindoostan – the bravest of the brave – Python sorceress of mighty power’. She wears a tight bodice, armlets, necklace and hoop earrings. The circus in questions was that of P. T. Barnum who combined with the Great London Circus and ‘the Ethnological Congress of Savage Tribes’. Maladamatjaute also inspired others to become snake charmers according to an article in the The World (March/April 1888). Snake charmer, Miss Ida Jeffrey from New York, tells how she ‘saw the famous Dama Ajanta, the Hindo girl who charmed snakes here (Madison Square Garden, New York) some years ago. She was tall and lithe and almost as slender as a snake. Maladamadjaute must have travelled widely since she appears in a Folies Bergères poster under the name of ‘Nala Damajanti – Charmeuse Hindoue’, circa 1890, while also performing for many years in the Adam Forepaugh Circus in the United States. As her fame grew, she continued to perform internationally in Europe and the United States under slightly different stage names. Despite this, the representations of her thick, full head of black wavy hair parted in the middle, and element of her ‘Hindoo/Oriental’ dress-jewelry, necklace, tight bodice, and hoop earrings remain constant. She and Breitwiser were married for a long time; he lived to ninety-four and died around 1930.