While the artist’s identity of 99,9 % of classical African artworks is unknown, in a few instances his or her name got recorded for posterity. While a sculptor would virtually never sign his work*, some artists became so famous that their work got documented by art historians. Stylistic comparison with the attributed sculptures, then makes it possible to identify even more artworks by a certain hand. In our current exhibition we are therefor excited to include a work by the Ghanaian artist Osei Bonsu (1900-1977), the most important Asante carver of 20th century Ghana. Bonsu served three Asante Kings and provided regalia for many other Akan paramount chiefs across much of southern Ghana during an active career spanning nearly sixty years.

(* a notable exception being the Zande sculptor Songo, as discussed in my book UNU (Brussels, 2023))

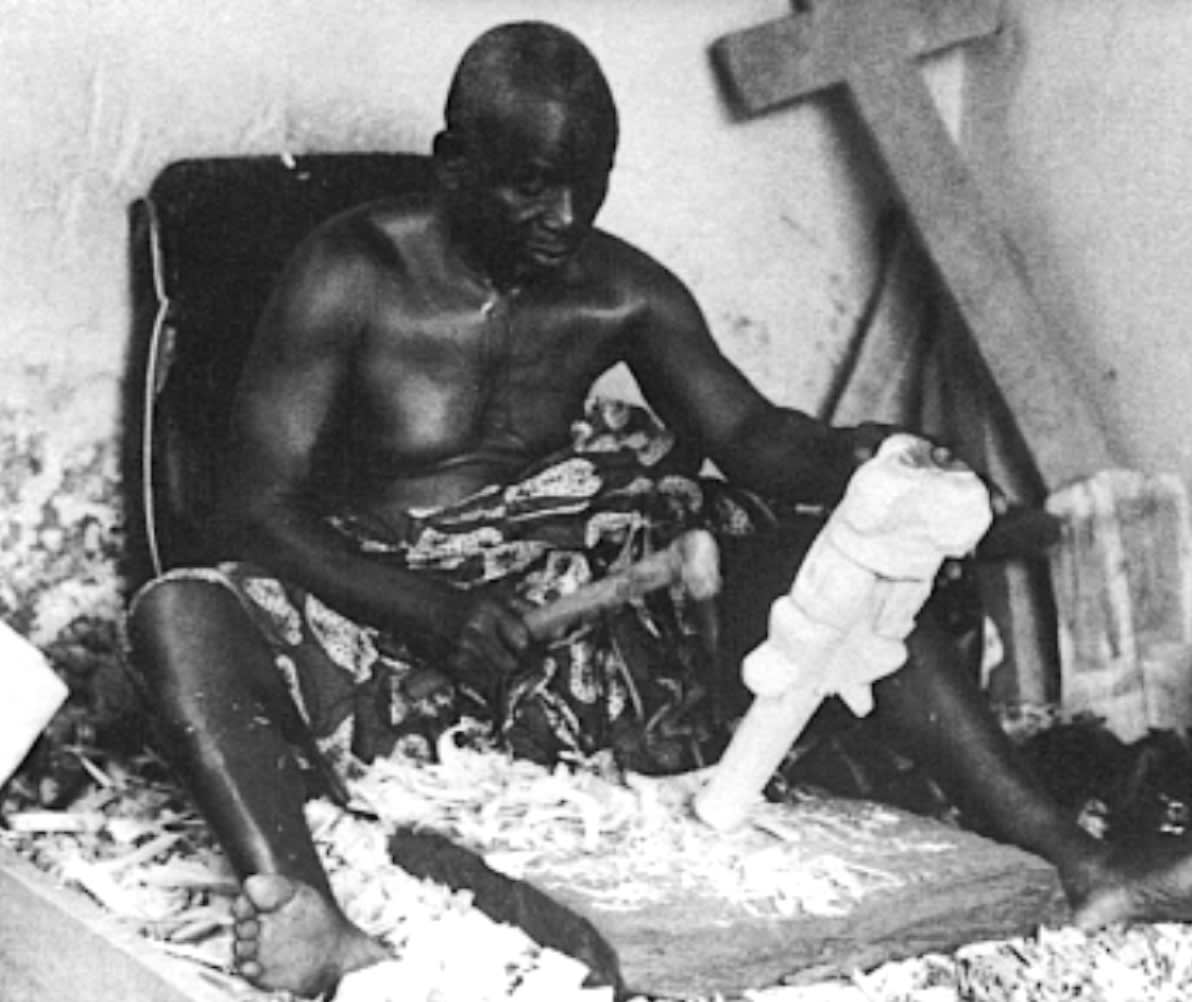

Osei Bonsu carving a staff finial, photographed by Doran Ross in Kumase in November 1976, one year before his death. (published in “The Art of Osei Bonsu”, African Arts, 1984, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 38, fig. 25)

In 1984, the American scholar and Akan specialist Doran H. Ross dedicated a whole article on the artist in African Arts magazine (“The Art of Osei Bonsu”, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 28-40). Other well-known anthropologists, such as Marion Johnson, Eva Meyerowitz (both 1937), and William Fagg (1968) have described and photographed his work as well. African art scholars such as William Bascom and Frank Willett also worked with Bonsu and commissioned sculptures from him, while with his wide knowledge of Asante art and culture he was an informant for many others beside Doran Ross. This broad attention from scholars is a clear measure of Bonsu’s important place in 20th century Asante art history.

Osei Bonsu was born in Kumase October 22, 1900, the son of Kwaku Bempah (d. 1936) and the grandson of Asantehene Mensah Bonsu (r. 1874-83) – a supreme chief. Bonsu’s father was both a drummer and a carver, learning the latter art in the palace from court sculptors. Taught by Bempah, Bonsu began carving at the age of ten and worked as an apprentice of his father until he was seventeen. Beginning in 1920, Bonsu, his senior brother, and their father were employed by Captain R.S. Rattray as informants and carvers, accompanying the anthropologist throughout many parts of Asante. The father and brother travelled to England, for the British Empire Exhibition in 1924, while Bonsu remained home and received several important commissions from Asante chiefs. The next fifteen years were among the most active, and many of his best carvings date from this period, 1925-1940 (Doran Ross, op. cit., p. 30). The distinctive “egg-shaped” head of our statue is typical of Bonsu's carvings from about 1935 to 1940, so it may have been carved shortly after the restoration of the Asante Confederacy in 1935 when many chiefs competed with each other to amplify their visual presence at festival displays.

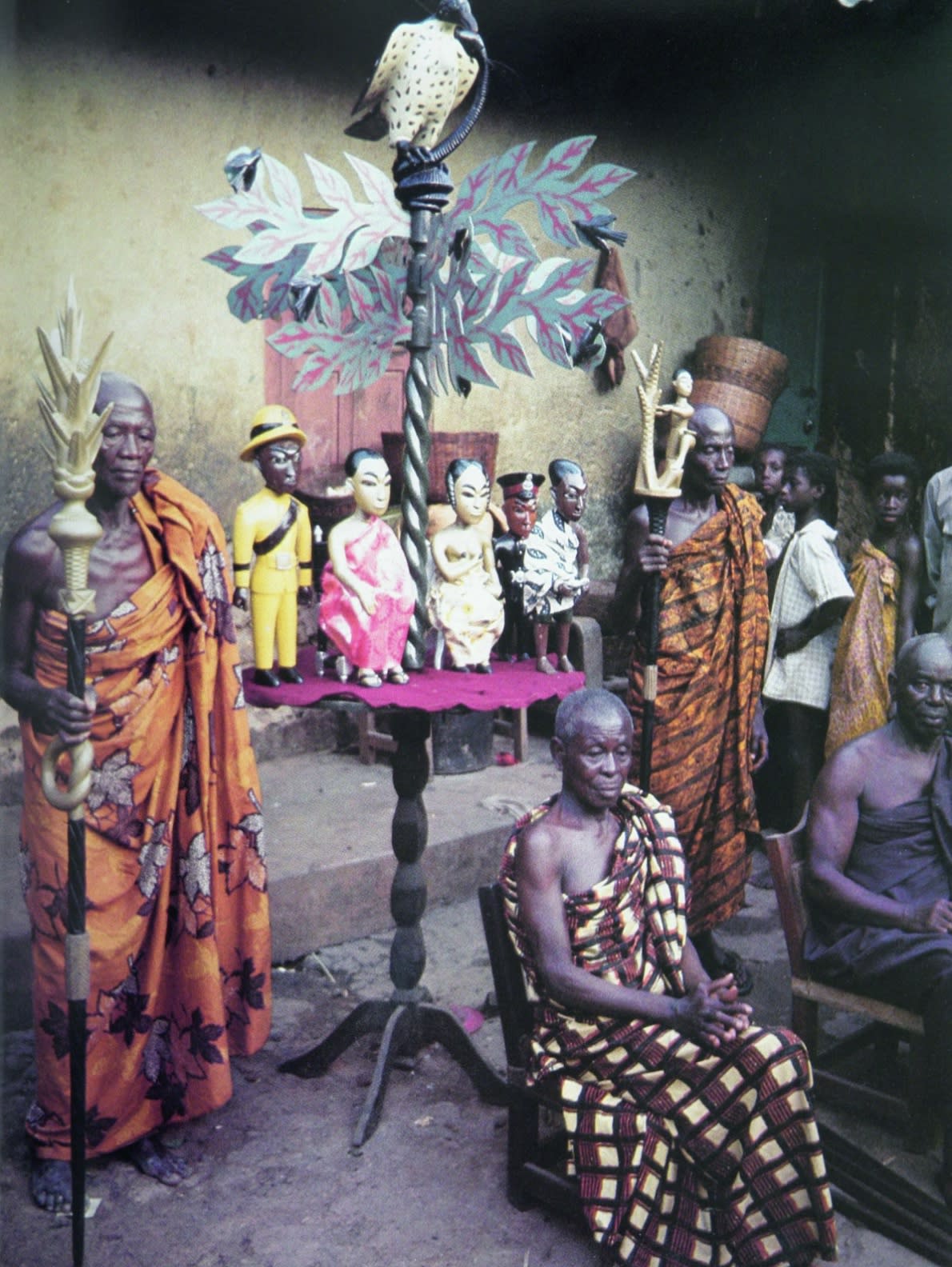

A display ensemble of figures carved by Osei Bonsu in 1933 and photographed in the 1970s. Bonsu is seated on the right. Published in: Cole (Herbert M.) and Doran H. Ross, "The Arts of Ghana", Los Angeles: Regents of the University of California, 1977, p. 177.

In all likelihood our figure once formed part of a display ensemble of figures, as illustrated above, on public view during Ntan performances. Ntan bands were popular among the Asante between 1920s and 1950s and performed on occasions such as naming ceremonies, weddings, funerals and traditional festivals. The term Ntan referred to the entire event that featured music and the display of carved figurative sculptures representing the chief, queen mother and members of the court (such as bell ringers). Reflecting the colonial presence of the times on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), these sculptural groups also often included figures of colonial officers. This group of wooden statues were often doweled onto a table featuring an elaborate carpentered tree. The whole formed a stage set that was put in place near the Ntan drum at the beginning of the performance and taken down when it was over. The figures’ function was to enhance the display and impress the onlookers while communicating and confirming society’s hierarchies. Osei Bonsu articulated to Doran Ross that he was the first to carve these figurative scenes specifically for Ntan drumming groups in the late 1920s. In 1976 Bonsu named 53 villages or towns where he had carved Ntan drums with their accompanying figurative scenes between 1926 and 1940, when he made his last drum set. Bonsu told Doran Ross that on the average it took him a month to carve a full set of figures along with the drum.

Left: our figure. Central: an almost identical standing figure with its original dress still preserved – explaining the color difference noticeable on the body of Duende’s statue. Height: 35 cm. Sold at Etude J.J.Mathias-Baron Ribeyre-E.Farrando, Paris, "Collection Michèle Yoyotte", 6 October 2016, lot 397. Right: a younger statue by Osei Bonsu (circa 1960), with a similar hand position and still holding the original wooden court bell. Height: 35 cm. Sold at Zemanek-Münster, Würzburg, "Tribal Art Auction 90", 17 November 2018, lot 166.

Typical for Osei Bonsu’s unique style are the oval, almost egg-shaped heads, that, when compared with other classical African carved figures, are only slightly oversized. Female coiffures are generally elaborate and elegant, while male hairdos are simple and occasionally only suggested by paint. Characteristically there is a high sloping forehead rising from pronounced eyebrows, with almond-shaped eyes dominated by a projecting upper lid. The straight nose is rarely prominent and lacks flared nostrils. Set low on a pointed jaw is a small slit-like mouth without well-defined lips. Necks on both males and females generally are ringed. Rounded shoulders slope downward to relatively small hands, and the feet are likewise small and lacking detail. Overall Bonsu’s figures are well-rounded and feature a carefully finished surface. Very few of his carvings display the traditional Asante vegetable paint from roots; most of his freestanding sculptures are completely covered with commercially produced gold paint or other multicolored enamels. All things considered, Bonsu’s carvings are among the most naturalistic of those created by Asante artists. (Doran Ross, op. cit., p. 32).

Group of Ntan statues carved by Osei Bonsu in 1933; notice the two bell bearers on the front row. Photographed in Ghana by Doran Ross in November 1976 in Aduamoa; published in: Cole (Herbert M.), "Maternity. Mothers and children in the arts of Africa", Brussels, 2017, p. 221, #196

Left: Maternity figure by Osei Bonsu. Height: 44 cm. Collection Seattle Art Museum (81.17.323). Right: Staff finial by Osei Bonsu. Height: 42,5 cm. Collection Yale University Art Gallery (2006.51.175).

Besides carving for Ashanti nobility, Osei Bonsu also worked as a sculpture teacher in three colonial schools, enabling him to work full time as a sculptor. When Prempeh I returned from exile in 1924, he helped with reinstalling the throne regalia and with the reconstruction of the sacred Golden Stool. The ascension of Prempeh II to the throne in 1931 enabled him to acquire a number of commissions from the court and later also from that of Opoku Ware II in 1970. Sojourns in Accra and Cape Coast, where he stayed afterwards, allowed him to also work for other Akan courts, but after independence, when the ill‐famed Kwameh Nkrumah took over, he fell into disgrace for unclear reasons and was detained in Usher Fort until the 1966 coup. The statue on display at “Echoes” is a textbook example of the master’s unique style and we are happy to notice it is one of the visitor’s favourites.