PANEL, MGBO EZI

Anonymous Igbo artist

Nigeria, Early 20th century

Wood, metal. 121 x 45,5 x 2,5 cm

Provenance:

Emile Deletaille, Brussels, Belgium

Native, Brussels, Belgium, 2014

Private Collection, Antwerp, Belgium, 2014-2023

Duende Art Projects, Antwerp, Belgium, 2023

While Igbo architectural traditions have received little attention in the literature, their meticulously carved doors and panels can be celebrated as proper masterworks of art. Nancy C. Neaher is one of the few scholars who has studied the subject, and we’ll extensively quote her article “Igbo Carved Doors” which she published in “African Arts” in November 1981 (vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 49-55). It is impossible to write about the doors and panels from the northern Igbo of southeastern Nigeria without first learning something about the way their villages were once organized. The basic unit of an Igbo village community was the umunna.

Interior of a large obi in Nimo or Abagana, photographed by K.C. Murray, ca. 1950. Published in Cole (Herbert M.) and Aniakor (Chike C.), “Igbo Arts, Community and Cosmos”, Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles: University of California, 1984:71, #123.

Igbo temple with carved wooden walls and tin roof. Photographed during Bolinder’s expedition to West Africa (1930-1931). Collection Etnografiska Museet, Stockholm (0221.g.0059.)

Umunna signified a territorially based kin group of several families who remembered a common male ancestor. The village of Awka for example consisted of 33 umunna, each of which practiced exogamy and organized households according to a virilocal principle whereby nuclear families lived with the husband’s parents. Umunna neighbourhoods clustered around a central square (ilo), which served as playground, civic center, marketplace, and site of certain shrines. Depending on wealth and social status, families could live in reed-walled, palm-thatched dwellings or in more elaborate walled compounds housing several nuclear families. This latter type provided the architectural context for carved wooden doors and panels known as mgbo ezi. Earthen walls two or more meters high and about a third of a meter thick enclosed a spacious courtyard, a series of chambers located along the periphery, outdoor kitchen, and often a men’s house (obu) prominently located in the center of the inner court.

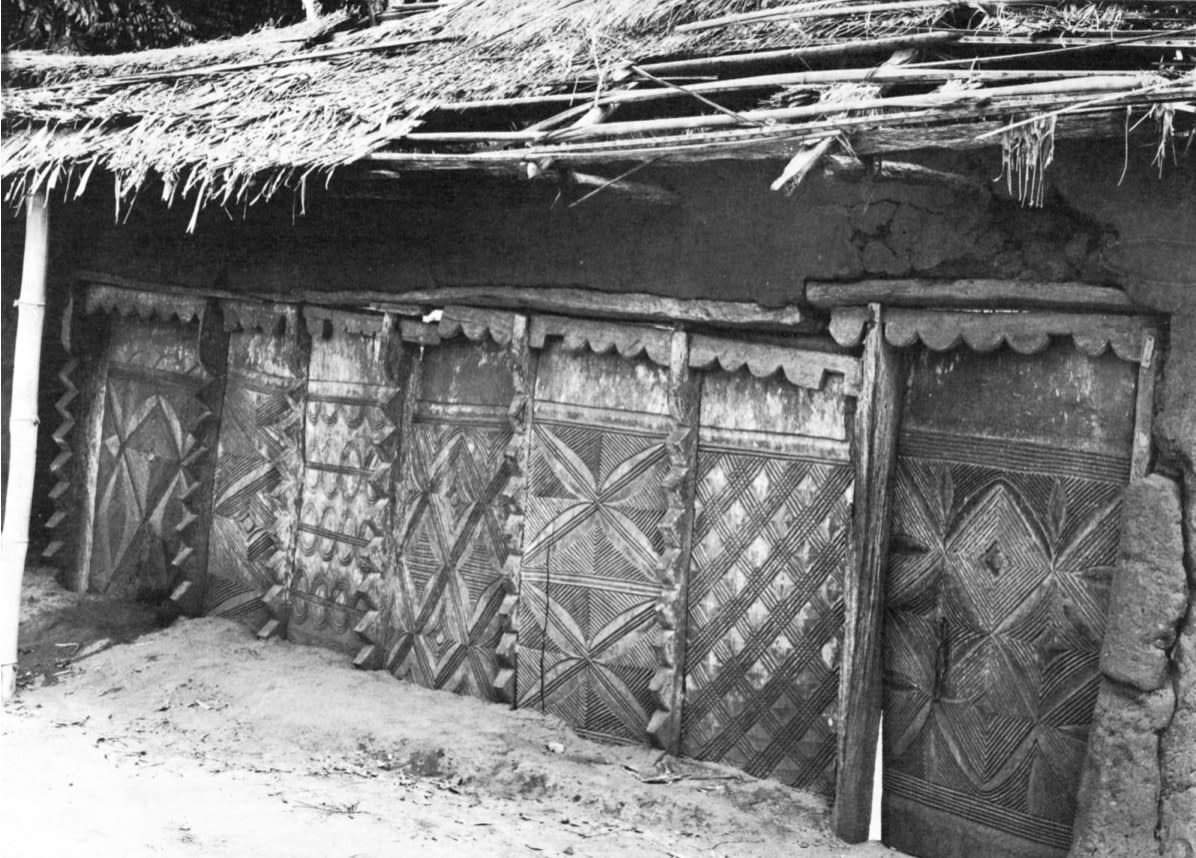

Igbo temple with carved wooden walls. Photographed during Bolinder’s expedition to West Africa (1930-1931). Collection Etnografiska Museet, Stockholm (0221.g.0060.)

Igbo panels and doors, photographed circa 1910 by Northcote Whitridge Thomas (1868–1936). Collection MAA museum of archaeology and anthropology (P.119850.NWT)

One or more slabs of African oak, widely known as iroko (Chlorophora excelsa; in Igbo as oji) formed wall and door insets at the entryway of the main compound. The large planks were extremely difficult to cut from the dense wood of the iroko tree and measured approximately 1-1.5 meters high and nearly a meter in width. Several individual panels could span the entry, with one acting as a door that swiveled on fixed pivots. A pull cord or iron chain affixed to its center served as a doorknob. Individual units were secured in an upright position with iron clamps joined to vertical supports and lintels. These ensembles differed from ordinary portals not only because of their size but also because of the rich designs carved in relief on their public side. Each panel was decorated differently, yet mgbo ezi are unmistakable for their unity of geometric patterning. Diamonds, squares, rectangles, and triangles are juxtaposed on fields of rich textures created by narrow grooved hatchings and tiny, dentated studs. Symmetrical distribution in grids accentuates the ordered precision typifying mgbo ezi designs. The repetition of striations, curved and angular, lends to the ordered precision typifying mgbo ezi designs. The repetition of striations, curved and angular, lends to the surface an illusion of compressed energy, resulting in oscillating rhythms reminiscent of Op Art illusions. The diminutive serrations and elongated lines catch and reflect light with the full strength of the sun’s rays. (op. cit., pp. 49-50).

Left: Height: 112 cm. Collection British Museum, London, UK (AF.45.545). Donated to the museum by P. A. Talbot. Published in: “Africa: The Art of a Continent”, Phillips (Tom), editor, Munich/New York: Prestel, 1995, p. 389, #5.53. Right: Private Collection. Height: 146 cm. Sold at Cornette de Saint Cyr, Paris, 14 April 2015: Lot 201.

These doors and panels once were the prerogative of highly ranked members of the prestigious northern Igbo men’s association, ozo. Men aspired to ozo and attained membership by fulfilling certain social, ritual, and financial obligations, gradually passing from lower to more exclusive upper of membership. Among other things ozo involved the acquisition and display of various kinds of paraphernalia: headgear, jewellery, ivory tusks, stools, staves; all of which became increasingly costly and elaborate as one ascended its ranks. Those who succeeded in reaching the pinnacles of ozo, usually in old age, were entitled to commission sculptors to carve mgbo ezi. While the precise rank could vary from community to community, all entailed enormous expenditures for lavish feasts and the payment of the carvers, who derived their main source of revenue from such commissions. In addition to those at the main entrance to the compound, these panels could also be placed within the ozo member’s obu or as enclosing wall panels on one or more sides.

Traditional Igbo doors, from the entranceway to a compound in Enugu-Ukwu, along the Awka-Onitsha Road, mid 1960s. Published in: “Traditional Igbo Art: 1966”, text by Frank Starkweather, Ann Arbor, MI: Museum of Art, University of Michigan, 1968. The six panels on the left are stationary. The gate is on the right. These impressive panels are set in a mud wall which surrounds the yard of an important family.

The obu, a focal point in the spatial organization of the compound, was the privilege of ozo men, a combination sleeping quarters, reception chamber, and personal and family shrine. With mgbo ezioften lining the walls or stored in the rafters along with other prized heirlooms, the obu gave physical and spatial presence to beliefs in the social and ritual primacy of senior men of the umunna. It was crucial for families to maintain harmonious relationships with their ancestors, a task reserved to these men of the umunna who were closest to death itself. Since only a minority managed to achieve ozo status, the imposing panels, spanning the main entrance or placed within the obu, acclaimed the extraordinary accomplishments of a member of the family. The importance of male elders to the life of the compound couldn’t be underestimated. Householders and their children looked to the senior resident as the authority on all serious family matters and revered him as the link to the ancestors and spirits enshrined in his obu. The senior man was also the most likely compound inhabitant to hold a title, so ozo rank most often coincided with family headship. Ozo membership amplified the rights as well as the burdens of leadership. (op. cit., pp. 50-52)

Left: Private Collection. Height: 83,5 cm. Sold at Zemanek-Münster, Würzburg, 3 March 2012. Lot 180. Right: Private Collection. Height: 140 cm. Sold at Material Culture, Philadelphia PA, 23 February 2022. Lot 303.

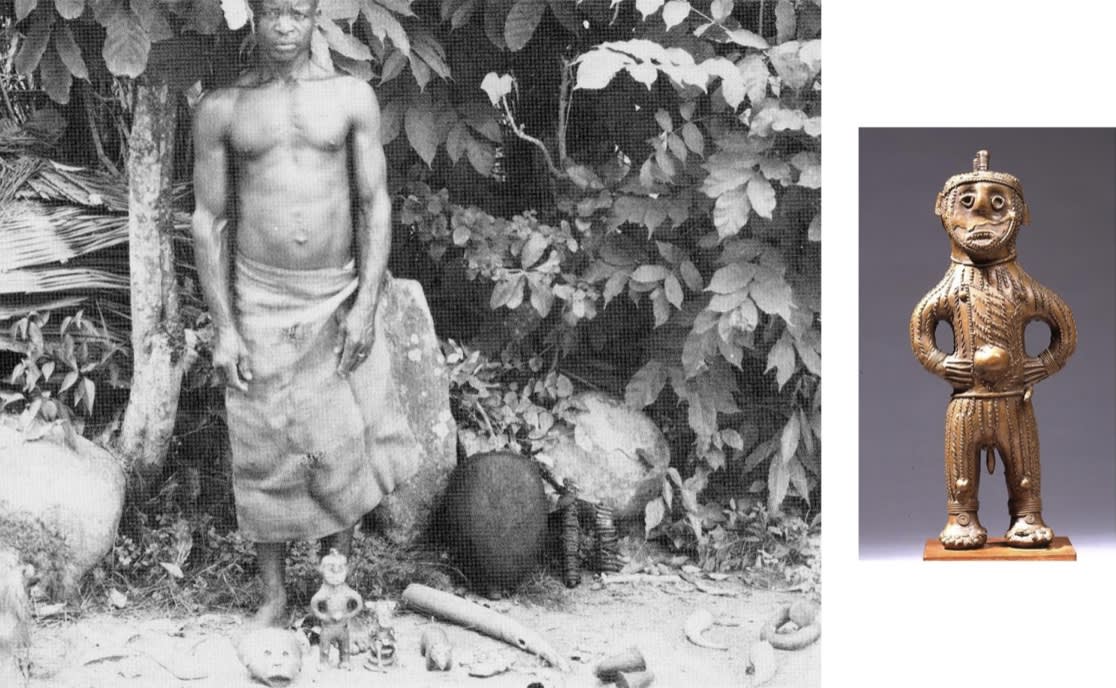

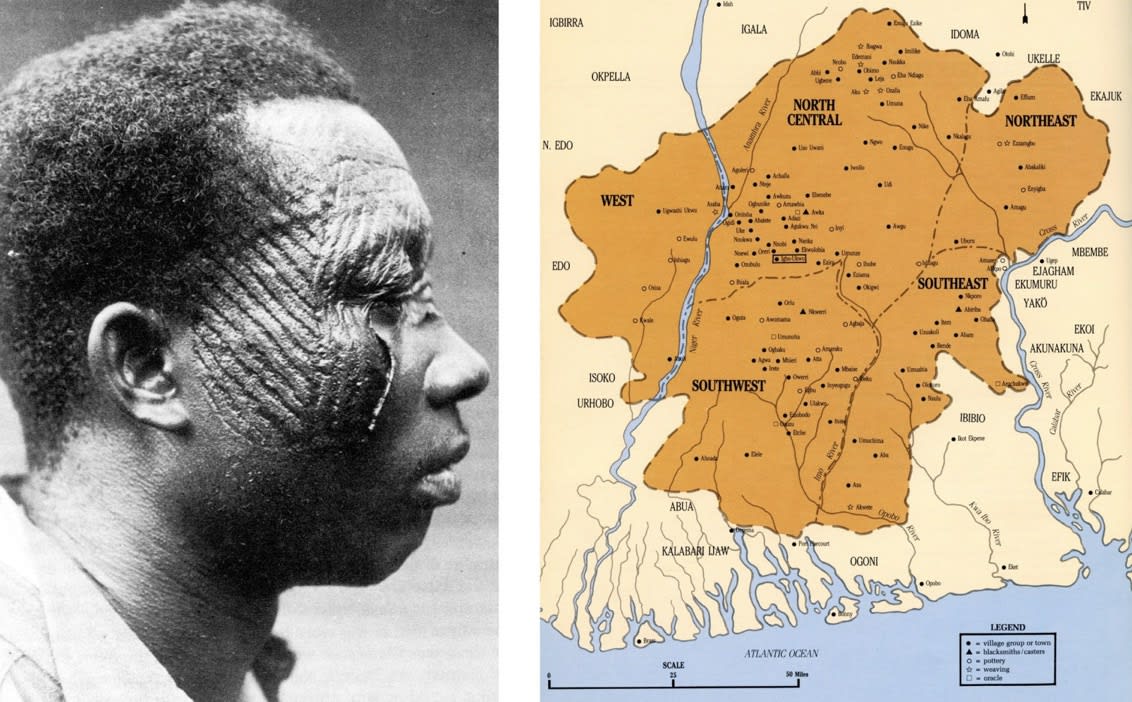

Mgbo ezi are distinguished by the careful carving into V-shaped grooves and the contrasts of plain with densely carved areas. In his book ‘Niger Igbos” (London, 1966, p. 316) Basden was the first author calling the typical sculpting style “chip” carving. Neaher hesitated to employ the term since for her it evoked the ancient Viking/Celtic decorative device of curved lines of V-shaped indentations on metal jewellery. In contrast, Igbo patterns were quite varied. However, John Boston in his book “Ikenga Figures among the North-west Igbo and the Igala” (London, 1977) also used the term, while differentiating northern Igbo sculpture in a ‘chip’ and ‘smooth-plane style, and ever since the term has been continuedly used to describe the region’s typical woodcarving style. Neaher has suggested that the typical relief carving possibly is inspired by the northern Igbo tradition of facial scarification. Such itchi marks consist of a series of narrow parallel lines incised on the forehead and temples of initiated northern and western Igbo men. As the initiation of young men into ozoincluded the itchi cutting, the facial scarification proclaimed high rank, while also being instrumental in the attainment of this position. According to Neaher, Itchi’s unique design of hatched lines recurs in the sculptural arts, suggesting a shorthand for masculine achievement and excellence. The foreheads of human statues indeed sometimes bear itchi, while the striated patterns on ozo stools, bowls, and other ritual objects appear to allude to itchi as well. Itchi’s extension to titled door panels, as fields of striated grooves, could accord with these usages. (op. cit., pp. 52-53)

Left: Itachi facial marks on an Isuama Igbo man, published in Jones (Gwilym Iwan), “The art of Eastern Nigeria”, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984:37, #5. Right: The Igbo and their neighbors, showing the major regions. Some towns or village groups are identified with symbols indicating their specializations (From: Cole (H.M.) & Aniakor (C.C.), Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos, Los Angeles, 1984: VI.)