For the occasion of Mostaff Muchawaya's first solo show outside Africa we asked the renowned South-African art critic Ashraf Jamal to write about the artist's captivating paintings. In his text Jamal eloquently captures the essence of Muchawaya's unique works. If you read one text today, make it this one - you'll definitely will look differently at Mostaff's brilliant paintings afterwards.

"Pathfinder" - by Ashraf Jamal

Oil, ink, found objects on canvas – the combination of materials in Mostaff Muchawaya’s art remains jarringly familiar. They speak to collage, the ready-made, a century-long resistance to transparency – to German Expressionism in particular, the great detractor which placed the artist’s war-torn psyche at the centre of an agonised drama, and drowned art in its lurid artifice.

Muchawaya’s art – part painting, part collage, wholly assemblage – bears all the traits of a Modernist tradition that thrust inward, and refused the mimicry of Realism or its more spectral variant, Impressionism. Instead, the frontier which modern art would claim was the fathomless interiority of Being. It was inside this precarity that Modernism, we are told, installed its Godless doubt. However, we forget that many of the early Modernists were theosophists, mystics, dreamers. What the new art of the 20th century issued forth was a wildly eclectic set of belief systems, which were irreducible to any orthodoxy.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Untitled", 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 167 x 182 cm

That, today, we find a great return of the core drives of Modernism – in the stratospheric return of Abstraction, for example – tells that we are not done with all our exploration. Indeed, as T.S. Eliot reminded us in ‘Little Gidding’, the last of his Four Quartets, ‘We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time’. This view is powerfully echoed in Muchawaya’s exhibition, Mutsvagi Wenzira (Pathfinder), in which this sense of an eternal return is acutely felt. As Muchawaya reflects, ‘From memories of my upbringing, from where I came from up to now, I find myself’.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Self-Portrait", 2017. Acrylic paint on hardboard, 81 x 96 cm

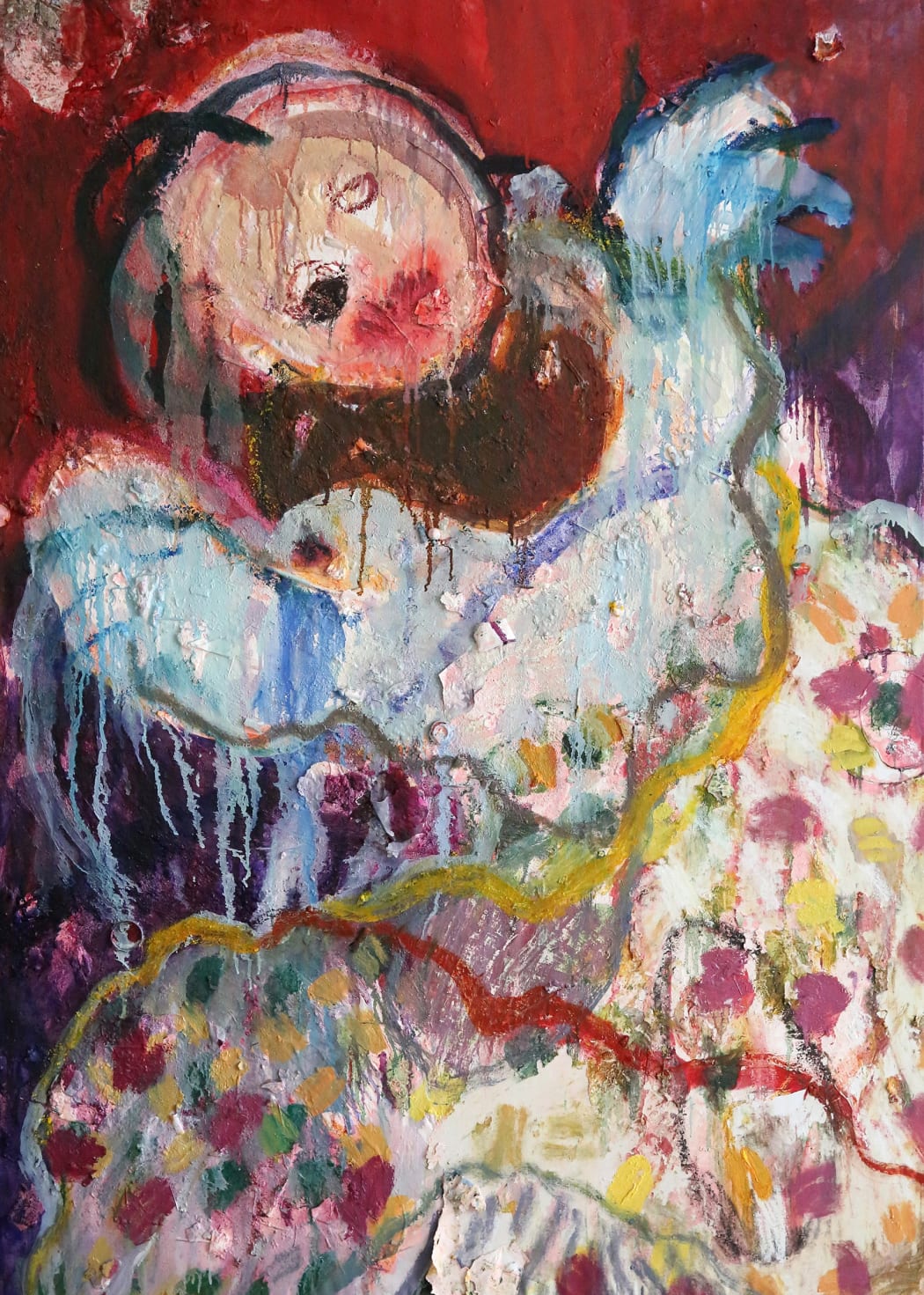

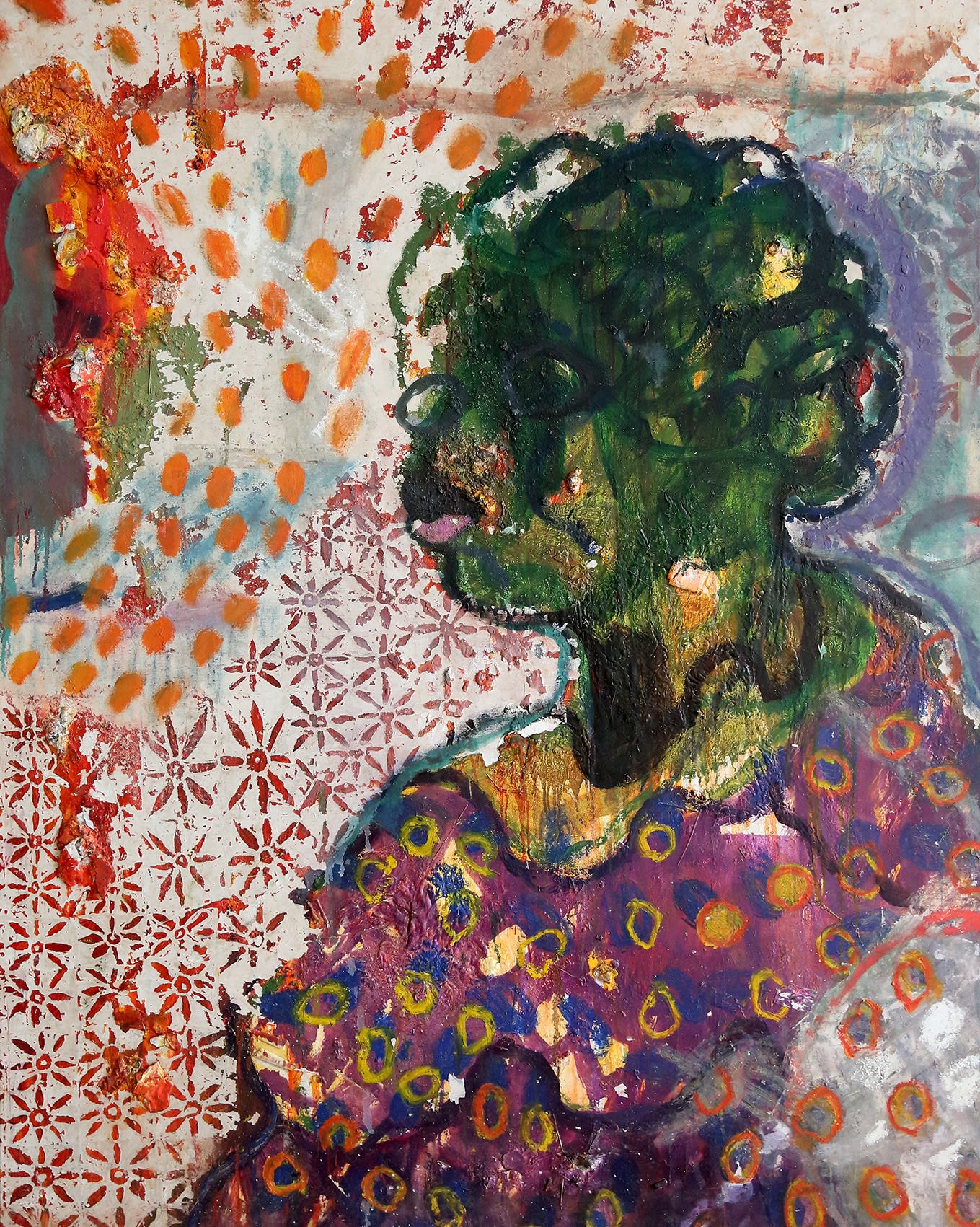

Encountering a Muchawaya relief work, it is this eternal return one senses – and age-old truth spliced with the giddy pleasure of novelty. Despite the fact that he is an African artist in a time in which Black Portraiture is the rule, he has refused the iconicity of the black body in the artworld, in favour of presenting a more psychic depiction of black being, or more controversially, a being more generally, more inclusively – universal. This is the way of the ‘pathfinder’ – the one resists arbitration, preferring to give us paintings in which the bodies conjured are largely consumed by a painterly aesthetic that overrides, deletes, or smudges out any realistic depiction. His ‘Self-Portrait’ (illustrated above), for example, is a pairing of black and white figures, inverted echoes, skewed doppelgangers. His ‘Untitled Portrait’ is a crude rub of circles for head and eyes and an ovoid thrusting red tongue. This is less an iconic representation of black resistance, more challenging resistance – with tongue thrust out – to those who seek to keep the black body a bondage, while casting it in the guise of freedom.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Rutendo", 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 166 x 118 cm

Abstraction is the dominant register in Muchawaya’s paintings. In this regard, they are timely. Visit any major contemporary gallery in Europe today, and it is Abstraction which graces or haunts its achingly white walls. Why? Because we are not done with it, despite all attempts to thrust it under the carpet. Because we are traumatised, caught in the stranglehold of grotesque piety and righteousness, bonded to some or other political dogma, wracked by identity politics, sickened by guilt, and fundamentally drained. Thus, it is unsurprising that what we seek, and find most therapeutic, is art that refuses to explain itself, that asks only that we linger longer, embrace a calming colour field, or some vivid hemorrhage.

Matisse was correct when he declared that we want nothing more, after a long day at the office, than to kick off our heels, sink into a comfortable armchair, and enjoy a lovely painting. If Muchawaya fulfils this brief today, it is not because his paintings are pretty, but because they mirror our shredded exhaustion, and appease us in the midst of this recognition. This is because we cannot deny ugliness, or error, because we now find ourselves caught at a radical juncture – between hope and its impossibility. This is our psychic crisis, which Muchawaya presents to us. Through his paintings we too can find ourselves.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Chimwanda mountain near Nyazura", 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 201 x 168 cm

All eras have their creative seers, their confessors, or soothsayers. In today’s starkly abrasive and haunted world, we require art that is psychically honest – this is Muchawaya’s gift. His abstracts are especially restorative. We are drawn to their crudity, discordant choreography, yet tonal gentleness. One work, titled ‘Chimwanda Mountain Near Nyazura’ (illustrated above), speaks to geography. However, as to the scale of the geography evoked? It is impossible to say. The artist’s vision is as microcosmic as it is macrocosmic.

A work, especially appealing to me, is ‘Gwinanzira Near Odzi’(illustrated below). Once again, the trigger is geography, but these are works that refuse a landscape format, rather, theirs is a psychic geography. Verticality is especially key in the seeming rockpile in slurries of pink and lilac. The one prevailing trait in all of Muchawaya’s works – which read as paintings, despite the accreted foreign substance, sometimes thickly, sometimes slightly, which are lodged into/onto them – is that they resist any definitive mark-making. Instead, what we are looking at are loosened blobs of colour, some psychic and seismic shift.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Gwinanzira near Odzi", 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 184 x 167 cm

Whether Muchawaya paints a human figure, or a landscape, one thing is clear – and that is the refusal of clarity. As to why this is the case? Perhaps because he can uncover none in its entirety, despite being a ‘pathfinder’? Because clarity is a ruse in these troubled times? Because his Africa is no curiosity, no fetish, that can be easily reified? Or because, as I’ve stated at the outset, we are compelled to revisit the damage we have caused, because no answers wholly lie before us?

In this confusing regard, Muchawaya’s portraits are refreshingly free of entitlement, or any self-justification. Rather, they haunt our peripheral vision, they will not be contained or mastered. Because they prefer the limits of cognition, the far reaches of taste, because in this world in which we find it difficult to digest the state of play all about, the terrible unease we feel, they are artworks which have deliberately and smartly resisted gluttony, or easy consumption.

Mostaff Muchawaya, "Untitled portrait", 2022. Mixed media on canvas, 207 x 165 cm

Ashraf Jamal is a Research Associate in the Visual Art and Design Centre, University of Johannesburg, and Writer-Researcher for ArtBankSA. He is the co-author of “Art in South Africa: The Future Present”, and author of “Predicaments of culture in South Africa”, “Love themes for the wilderness”, “A million years ago in the 90s”, “The Shades, In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African art”, and “Strange Cargo: Essays on Art”. His new book “Wide Ladder: Abstraction & The Figure” is forthcoming.