My last exhibition "Unsettled" was the perfect opportunity to present a number of African sickness masks, among which two deformed and unsettling Ibibio masks.

Among Nigeria’s Ibibio peoples, sickness masks were designed to instill fear among the population. Indeed, instilling fear was a powerful tool in teaching right from wrong. When someone was told, "You will be haunted for the rest of your life for that," or "Someday it will come back to haunt you” similar threats were made in order to let someone refrain from a certain type of bad behavior.

These Ibibio masks were used by the Ekpo society, a crucial instrument in the hands of the village chiefs that acted as an agent of social control in the absence of a centralized, political state. The duties of this society were to propitiate the ancestors for the welfare of the group, to uphold the authority of the elders, and to maintain order in the village. The enforcement of the rules and regulations affecting every aspect of day-to-day life were given powerful spiritual sanctity through the appearance of the ancestors through wooden face masks. A mask depicting a face ravaged by disfiguring tropical diseases horrified the pubic, striking them with terror, and proved a most efficient means to instill fear and respect for the Ekpo society.

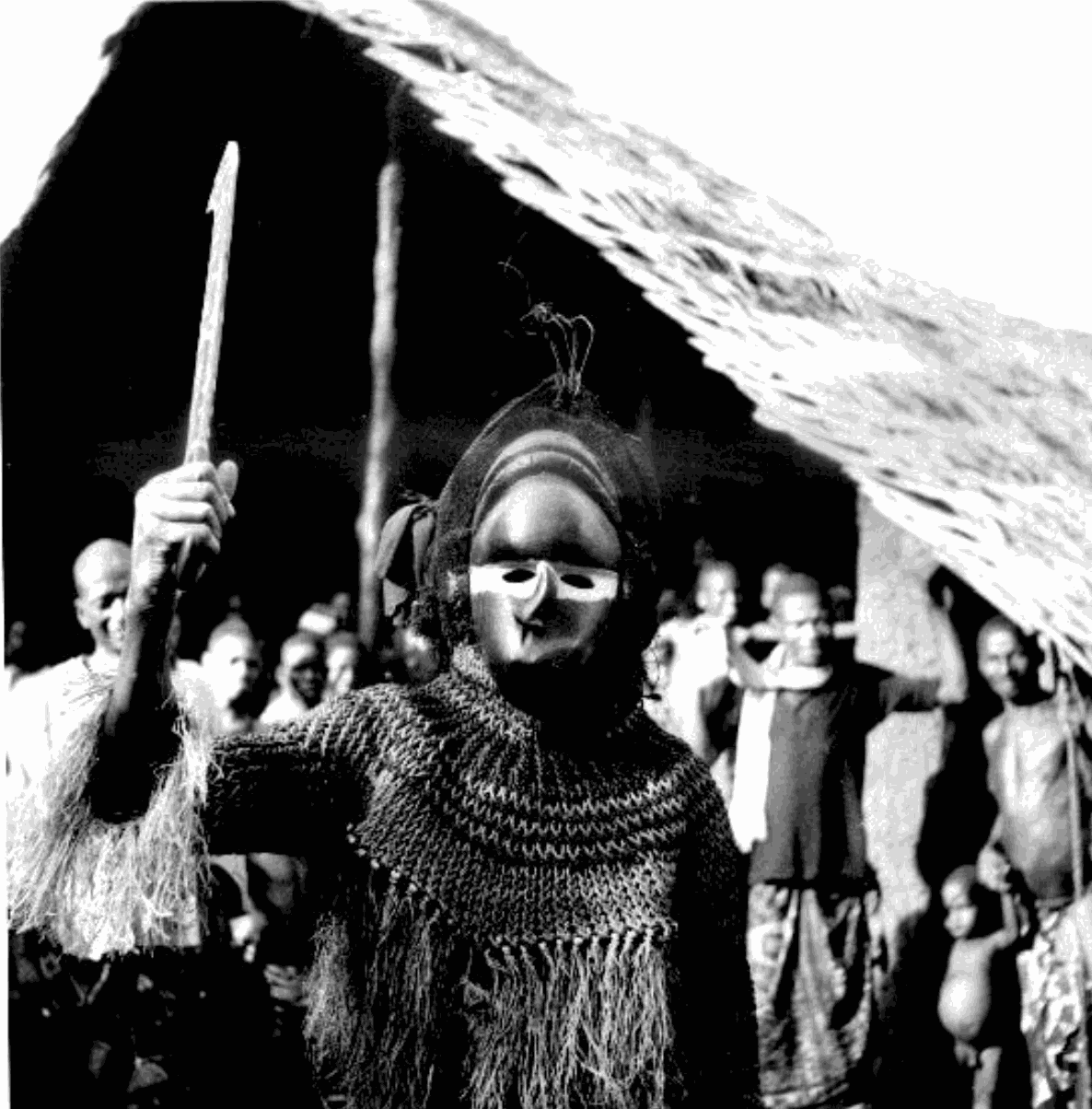

Ekpe (Egbo) Runner Uzuakoli with a similar sickness mask. Photography by G.I. Jones in the village of Uzuakoli, 1930s.

Ekpo, a person’s soul, either transmigrated to the underworld at death to await reincarnation or to become an evil ghost. Ghosts (ekpo onyon) were the souls of the dead that could not enter the underworld and were doomed to travel the earth forever, homeless, and alone. Such a destiny depended on the person’s earthly activities. For example, if a person was found guilty of a serious crime against the community, he would have been killed and his body thrown into the ‘bad bush’ where ghosts were believed to reside. If a person developed a terrible disfigurement, such as leprosy, smallpox, or gangosa, this would be considered to be divine retribution, in which case, at death, likewise, the body would be thrown into the so-called bad bush.

In Ibibio culture it was said that a doer of evil deeds would become an evil ghost (idiok ekpo). Every village had an Ekpo lodge, where all the society’s regalia, such as its wooden masks, were kept. Each community also had a sacred forest where the ekpo spirits were said to roam. Once a year, at the end of the harvest season, ekpo masks appeared for a period of about three weeks. The masqueraders accompanied the villagers singing and parading throughout the village. Each town had a number of open areas, focal points in the compounds of the main families, which were visited by the ekpo masquerades to pay their respects and perform. Women, children, and non-initiates were excluded from these performances. Additionally, on the first and last days of the harvest season a public performance took place at the most important marketplace. At this occasion, everyone was allowed to witness the dances. Once the idiok ekpo had arrived, the family leader drew a circle in the sand. Each new masquerader that came near the spot, was lured into the circle before performing – this was to invoke the spirits in the underworld to witness and guide the performance. The idiok ekpo masquerades queued up to perform, one after the other, before joining their fellow members. Eventually the entire group appeared, buzzing around the arena like angry wasps, lunging unpredictably into the crowds, and occasionally fighting each other, jumping, running, swirling with vivacious energy. The Ibibio recognized that once a mbop (mask) was put on, an ancestor’s soul (ekpo) possessed the wearer, so that the masquerader could commit any type of havoc without anybody questioning his actions.

Masked Members of the Egbo Society. Published in M'Keown, Robert L., "Twenty-Five Years in Qua Iboe: The Story of a Missionary Effort in Nigeria", 1912, fig. 65.

The styles of ekpo masquerade costumes and performances varied greatly from village to village. However, throughout the region the overall color for the idiok ekpo (“evil souls”) masks and costumes is black, to represent the fact that ghosts come out at nighttime. The masks had to be frightening in order to invoke the threat of force and authority necessary for the ekpo society to maintain order. The below face mask portrays a victim of a particular variant of the disease gangosa, which the Ibibio call ibuo-akwanga or “twisted-nose”. Gangosa resulted from a severe vitamin deficiency which destroyed the membranes of the nose. Its depiction was a reminder of the diseases sent as punishment to particularly evil lawbreakers. The distorted, deformed, and exaggerated features of this type of masks inspired many artists.

The British sculptor Henry Moore owned a very similar mask as the one above (Sotheby's, New York, "Henry Moore Artist and Collector", 14 May 1997, lot 333). As illustrated above, the British colonial officer G. I. Jones photographed a very similar mask worn by an Anang Ibibio ekpo dancer in the village of Uzuakoli in the 1930s. Several other masks from this workshop are known: one formerly in the prestigious James Hooper collection (Christie's, London, 14 July 1976, lot 72), another formerly in the Ratner collection (Drewal (Henry J.), "Traditional Art of the Nigerian Peoples", Washington, D.C., 1977, p. 45, #44), one sold at Sotheby’s in 1990 (Sotheby's, New York, 21 April 1990, lot 262). Other similar masks with a crooked nose are in the collection of the Antwerp Ethnographic Museum (AE.1959.0055.0037), Parisian Musée du quai Branly (73.1989.3.1), and Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco (#1979-03-06).

The French sculptor Arman owned a very similar mask as the one above (see "African Faces, African Figures. The Arman Collection", New York, The Museum of African Art, 1997, #61), which was exhibited at the BOZAR in 2010 during “GEO-Graphics: a map of art practices in Africa", curated by David Adjaye (p. 214). Both masks are still available, so please do get in touch if you would be interested!