Ever since Adenike Cosgrove published her yearly State of the African Art Market last month, I’ve been thinking about the comment one of the participants of the survey made:

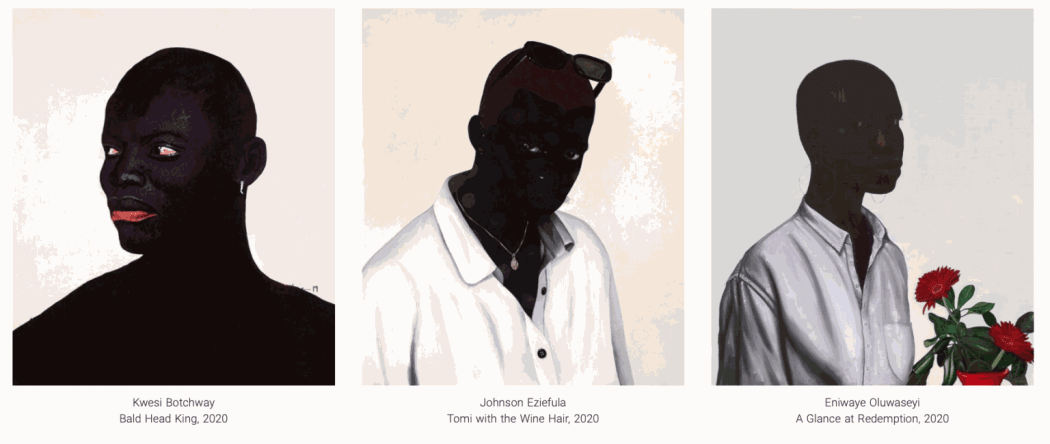

“The (African) contemporary scene is now flooded with mediocre portraiture and self-portraiture, narcissistic works turning on ‘identity’, formulaic flat-styled figurative painting and a lot of imitative work. This superficiality/commercialism is stoked by art fairs and frothy auction action that is mainly driven by wealthy and speculative buyers (including corporate interests) who have more money than taste or discernment.”

The above juxtaposition of three paintings just next to that quote seems to illustrate the collector’s point. Yet, I do disagree. Firstly, one can hardly state the emergence of portraiture celebrating blackness is something new. The African American artist Kerry James Marshall, who indirectly can be considered an influence on some contemporary African artists, has been building 40 years on an oeuvre focused on black self-representation. His 1980 work “Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self” for example features a black man dressed in black and before a black background. Through his work, Marshall has helped correct what he has called the “lack in the image bank of Black subjects”, and has paved the way for other artists such as Kehinde Wiley. Wiley, an American portrait painter with Yoruba roots, indeed has cited Marshall as a big influence. He is most famous for inserting black protagonists into a setting that recalls traditional European Old Master paintings. Kehinde Wiley’s fame got rocketed to a new level when Barack Obama commissioned him to paint his official portrait. Wiley depicted Obama seated casually on an antique chair among abundant foliage. With his art, the artist wishes to inspire future African American generations who visit museums and finally get to see someone who looks like them being displayed at its walls. In an interview with NPR, Wiley said:

“What I wanted to do was to look at the powerlessness that I felt as — and continue to feel at times — as a black man in the American streets. I know what it feels like to walk through the streets, knowing what it is to be in this body, and how certain people respond to that body. This dissonance between the world that you know, and then what you mean as a symbol in public, that strange, uncanny feeling of having to adjust for … this double consciousness.”

Hijacking traditional models of representation, reimagined with black models, Wiley’s work thus can be interpreted as a comment on the absence of black portraits in museums. His criticism of the art world has helped generate an emancipatory response among contemporary African artists.

Wiley’s brightly-coloured, one-dimensional backgrounds for example reemerge for example in the work of the Ghanaian artist Raphael Adjetey Adjei Mayne – who’s portrait of Amanda Gorman was recently donated to Harvard’s Hutchins Center (info). Mayne’s latest works, capturing and celebrating black experiences, are currently on view at the sold-out exhibition “The joy of my skin” at the Antwerp gallery Geukens & De Vil.

Image courtesy of Geukens & De Vil – photo by David Samyn, 2021.

It is fair to say there is currently indeed a wave of Black figurative contemporary artists specialising in portraiture. One of the leading figures is the painter Amoako Boafo, who after selling out a solo show at Art Basel Miami in 2019 became one of the most coveted contemporary African artists (a demand resulting in stratospheric prices at auction). Rendered with a distinctive finger-sculpted technique, Boafo’s portraits celebrate the Blackness of the subject. Portrayed against a light or monochromatic backdrop, the viewer’s attention is focused on the sitter.

The use of such monochromatic backgrounds to highlight the intensity of the blackness of the sitter perhaps should be considered a stylistical element of a whole new movement in contemporary African art. The list of talented artists who each give their own take on these aesthetics of representation is long: Cinga Samson, Collins Obijiaku, Kwesi Botchway, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, Sungi Mlengeya, Ephrem Solomon, and Annan Affotey all are raising interesting questions about black identity and representation. As always, self-portrait do speak multiple visual languages at once, drawing on the artist’s own multifarious identity as a painter, and generalisations should be avoided. Fact is that a whole new generation is exploring new interpretations on the sociological complexities of blackness and difference.

Cinga Samson. Image courtesy of Perrotin.

The work of Lynnette Yiadom-Boakye, who currently has a solo show at the TATE Modern (info), has been celebrated for its portrayal of Black normalcy. Yiadom-Boakye has frequently noted that her use of Black figures is merely drawing from her own inspiration rather than the critique of Western art’s relationship with Blackness some writers have projected on it. The artist thus already has moved ahead and in her own way is setting things right in the inequalities of visual representation in present day art world and its cultural institutions. Working with similar made-up empowering narratives as a frame for her portraits is Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, whose discovery of the work of aforementioned Yiadom-Boakye proved most inspirational to her own practice.

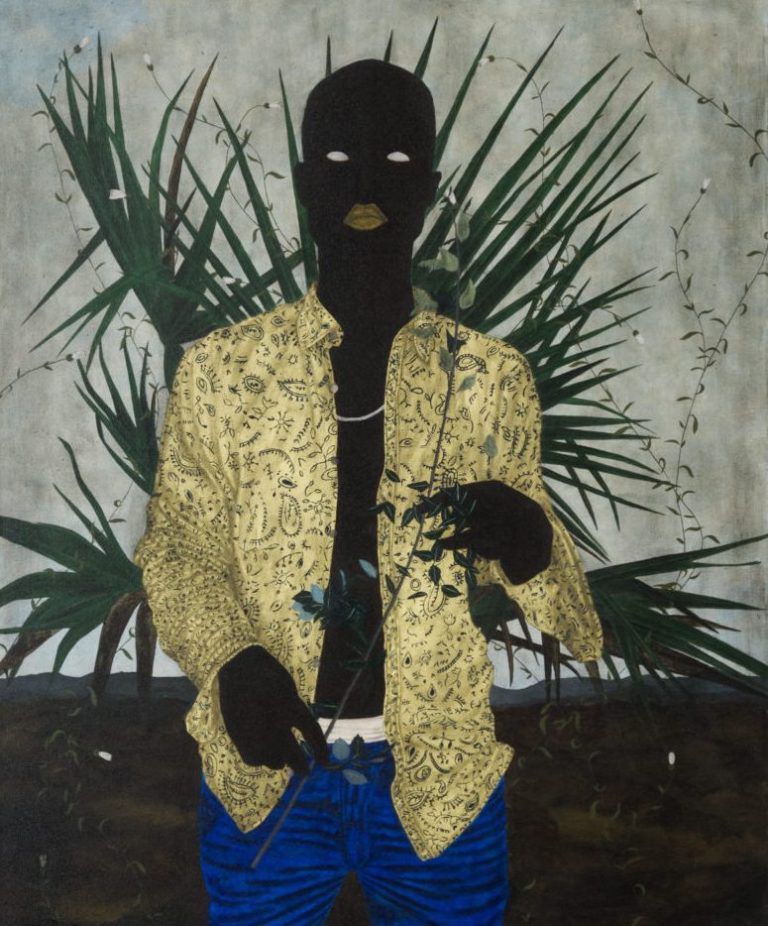

In the second half of the 20th century portraiture somewhat fell out of favour as a serious genre, yet Hwami and the other mentioned artists are helping to revive the genre while reformulating it around the Black body. Eventually this resurgence of figuration ‘will go beyond the Black body,’ Hwami said in an interview, ‘it will lift up portraiture as a genre for everyone. And that’s the beautiful thing about it.’

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Image courtesy of Victoria Miro.

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Image courtesy of Victoria Miro.