Begun nearly a century ago, the Vérité Collection astounded the world and shattered records when these treasures of African and Oceanic art came to market in 2006, and created a new benchmark at auction (selling more than 500 objects for almost € 44,000,000!). Imagine the amazing surprise today, 11 years later, that more masterpieces, the ones they kept, could emerge again as the last secrets of Ali Baba’s cave! It has been a fantastic journey to be able to work on this catalogue, which is now available online here.

Pierre Vérité (1900-1993) began collecting in the 1920s, at the dawn of French art market and a time when someone with a knowledgeable eye and a sharp sense could secure unimaginable masterpieces of African and Oceanic art. Like magicians, together with his son, Claude (b. 1928), they quietly ‘hid in plain sight’ and continued their collecting endeavours into the golden age of the 1950s and 1960s, with no one fully knowing the extent of their treasures.

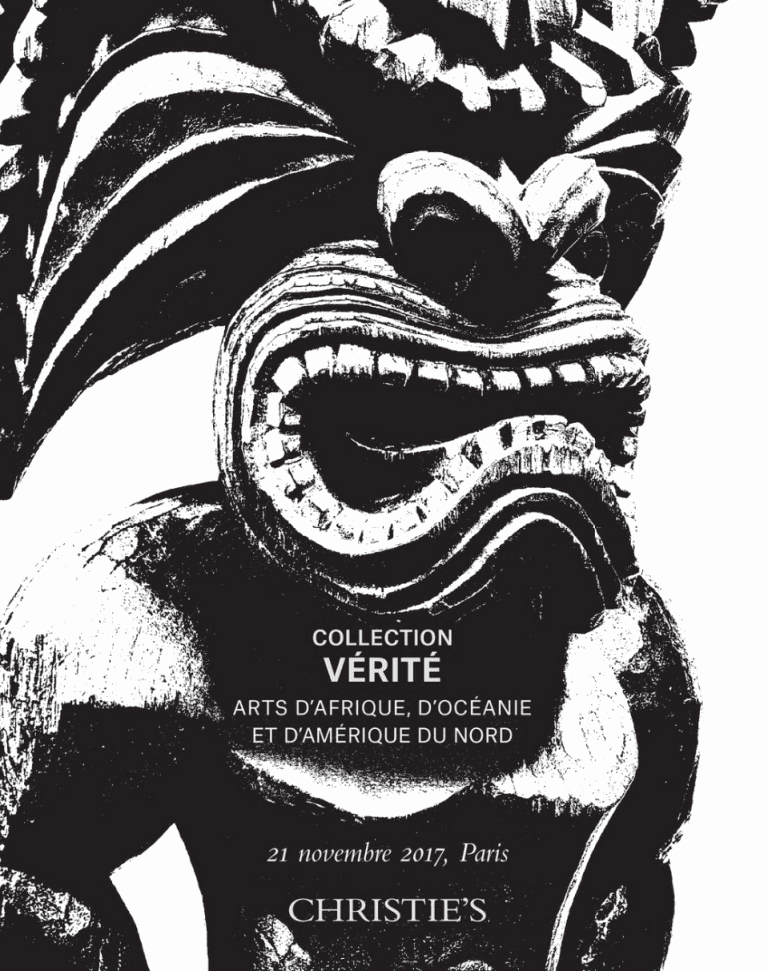

At the heart of this momentous strand of last pearls is the Hawaiian god figure (lot 153). A work that Claude Vérité always remembers from his childhood and amongst the most coveted. As with most of the Vérité works, its origin is unknown. Possibly found in the English countryside, or brought to the gallery in exchange for another ‘piece of wood’. What we know today is that is can now be appreciated amongst the greatest works of art ever created – equal on the great world stage to any other iconic sculpture to which it could possibly be compared. It was created at the apogee of Hawaiian sculpture during the late 18th century and the sovereignty of Kamehameha I, who associated himself with the great god of war – Ku ka ‘ili moku – whom this figure surely represents. His name means – land snatcher – and his power and purpose was fully aligned with the mission of Kamehameha I to so-called ‘unite’ the islands under his reign. This is what we now call the famous Kona style – a hallmark being the broad, figure-eight mouth, nearly extended tongue inside a prognathous jaw- also called ‘the mouth of disrespect’ – distended eyes and the posture of a wrestler. It is surely the same masterhand as another famous sculpture in the British Museum (LMS 223) collected by Tyerman and Bennett in 1823. Important to note that they are each carved from the same wood – metrosideros – or ohi lehua. A symbolic tree found only in the high mountains with red flowers and once cut the core looks like raw flesh.

Another major sculpture is the Walden-Kraemer-Loeb Ancestral Figure called Ulifor the Malangaan in New Ireland (lot 145). With its deep, black patina and tight posture and carving details, it is an archaic style of one of the most celebrated sculptural figures of the South Pacific – the ancestral Uli. As with most Vérité objects, it had a secret life. It was only in recent months that we unlocked its font of history and provenance – from its collection in a New Ireland village in 1909 to its home in the famous collection of Pierre Loeb – the important avant-garde modern art gallerist, scholar, voyager and collector of les ‘arts premiers’ – by 1929 to the last time it was seen in public in 1930. It was seen at the landmark exhibition at Galerie Pigalle, and as one of the few Oceanic works of art presented, it was featured in an editorial review of the show penned by Carl Einstein, another luminary of the early 20th century, a critic and historian who championed both modern and African and Oceanic art.

The magnificent range of Kota reliquary figures is of a level not seen together in public in many years – apart from what we can see at the current major exhibition at the Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac and featuring works of art from Gabon, ‘Les Forêts Natales’ – here in the Vérité collection we see 11 (!) variations on this classical, evergreen form appreciated for its abstract form, astonishing range of variation on a theme and the assembly of materials in wood and precious metals. From a Kota by a masterhand we could call the ‘Stieglitz Master’ for being the same atelier as another formerly in the collection of Alfred Stieglitz and now at the Musée Dapper – to a delicate Shamaye and Sango type – and a rare Mahongwe. The most important piece from this group is a Kota of the N’Dassa, which is estimated at €200,000-300,000 (lot 94).

Another amazing discovery is a beautiful and classical Hemba figure from the Democratic Republic of Congo (lot 115), representing a heroic ancestor among his clan. Apart from the famous Hemba in the Antwerp museum, very few of these sculptures made their way to Europe before the 1970s. It was clearly created by an important Hemba artist who thoughtfully made a signature style with diamond-shaped eyes, which are echoed in the shape of the navel – the center of the life and portal to the supernatural realm. In a chance discovery, we found that it was part of the landmark 1935 exhibition – African Negro Art – at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), when at the time it was part of the collection of Pierre Loeb. The catalogue entry demonstrates it was still an unknown style and he is simply referred to as being from Tanganiyka in the Congo.

Some history of the Vérité Collection:

In 1934, Pierre and Suzanne Vérité opened their first shop called – Arnod, Art Nègre – on the Rue Huyghens, in Montparnasse. The address, suggested to them by their friend and neighbour, the American artist John Graham, was illustrative of those early years and synergistic time when in 1916, the Lyre et Palette gallery, located a little further down the street, held the first Parisian exhibition that combined Modern art (Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani) with African art. Art dealers and collectors such as Paul Guillaume, Charles Ratton, Pierre Loeb and André Portier met and mingled at the Vérités’ gallery, alongside members of the Parisian avant-garde – the Surrealists Paul Eluard, André Breton and Tristan Tzara – and the international avant-garde, including Helena Rubinstein and James J. Sweeney, to whom Graham introduced the Vérités.

In 1937, they moved to the heart of Montparnasse on boulevard Raspail, and there Galerie Carrefour was born. More than ever, the Vérités were at the nexus of haute- Parisian cultural life in their salon. ‘Welcome to my forest’ – Pierre’s affectionate gallery greeting to his gallery and its inhabitants from Africa and Oceania – was likely spoken to the virtual constellation of 20th century modernists – Matisse, Picasso, André Lhote, Marcoussis, Breton, Eluard, Ernst, Derain, Lipchitz, Magnelli, Léger &c.

Pierre and Suzanne Vérité acquired most of the masterpieces of their personal collection during the 1930s, however their collection was not revealed to the public until 1950s when a few exhibitions came to light with works from their collection: 1951 at Galerie La Geintilhommerie, ‘Arts de l’Océanie’, 1952 and 1955 at Galerie Leleu, ‘Chefs-d’Oeuvre de l’Afrique Noire’ and ‘Magie du Décor dans le Pacifique’; ‘Art Afrique Noire’ 1954 at the Musée Réatu in Arles organized by such luminaries as Michel Leiris, Pierre Guerre, Charles Ratton, Pierre Vérité himself, and LeCourneur and Roudillon – here it was the last time that objects from the collection would be named as such. Later, though they remained generous in their loans and contribution to the academic knowledge of African and Oceanic art, their names only appear episodically, or not at all for instance the loan of the great Fang Ngil to the Museum of Modern Art’s ‘Primitivism’ in 1984 – anonymous.

The sale of the collection is on 21 November 2017 at 3pm and promises to be the event of the year; you are more than welcome to come preview the final treasures from this collection on:

15 Nov, 10am – 6pm

16 Nov, 10am – 6pm

17 Nov, 10am – 6pm

18 Nov, 10am – 6pm

19 Nov, 2pm – 6pm

20 Nov, 10am – 6pm

21 Nov, 10am – 2pm

I hope to see you there! Don’t hesitate to get in touch if I can be of any assistance.